7.1 Family policies in Japan

Japan has faced a rapid aging of the population, which is caused by both a decrease in the fertility rate and an increase in life span. In order to stop the trend toward a society with few children, it is necessary to create an environment favorable to child rearing.

The major reason behind the rapid fall in the birthrate is the situation whereby women have to choose between either continuing to work or quitting working and having children, and are not able to choose various working styles. The increase in temporary employees and long working hours made it very difficult for the Japanese to achieve the lifestyle and the working style they wished for1.

Due to criticism against the pronatalist policy during World War II, the Japanese policies at present to tackle low fertility are oriented towards promotions for gender equality, life-work balance, and support for families with children. The Gender Equality Bureau of the Cabinet Office is in charge of the family policy together with related policies run by other ministries such as the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare or Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Japan ratified various international conventions related to human rights. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 1985, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1994 were ratified. As a member of the international community, Japan improves various social measures for families.

7.2 Income support for families with children

7.2.1 Universal Child Allowance

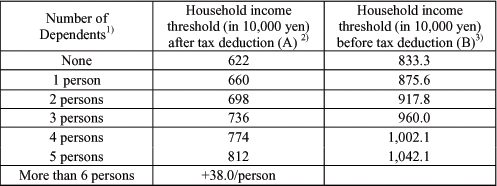

Under strong political initiatives, a new Act of Child Allowance was enforced in April 2010, and soon after in April 2012 it was amended and an income threshold was reintroduced. The amended child allowance is paid to households with children up to 15 years old, with the income threshold as listed in Table 7.1. The amount varies from 5,000 yen to 15,000 yen according to the age of children and the income level of the households.

Table 7.1 Income Threshold for Child Allowance (2012)

1) The number of Dependents include a spouse and other family members who can be eligible to receive income deduction under the tax act.

2) Annual Income of previous year (unit: ¥10,000)

3) (A) +tax exemptions = (B)

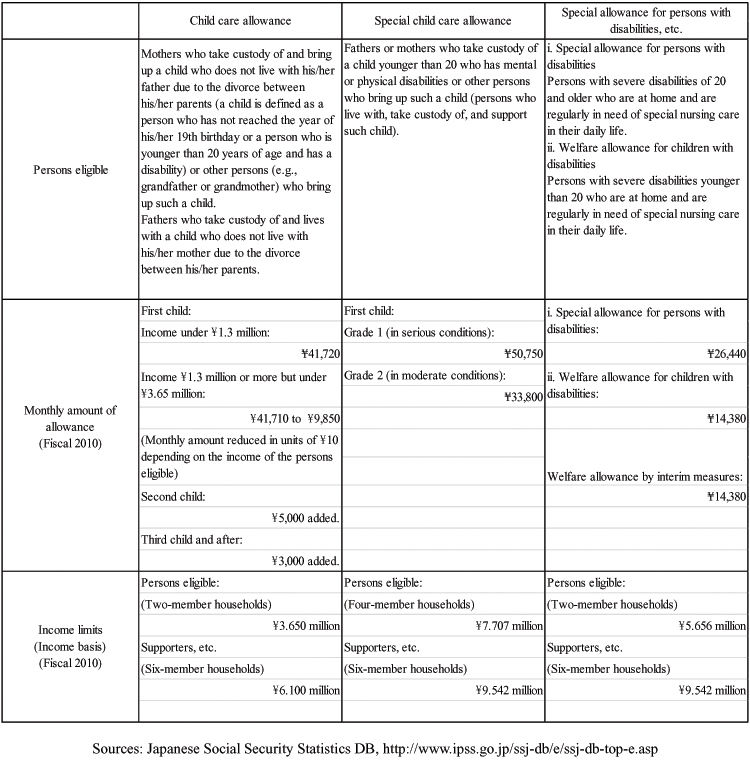

7.2.2 Child Rearing Allowance (for single-parent households)

The Child Rearing Allowance is given to a single-parent with limited income who is rearing a child/children of 18 years old or younger. The monthly allowance is ¥41,430 in the case of one child, ¥5,000 for the second child, and an additional ¥3,000 for each child including the third and subsequent children (2012). Before August 2010, only single-mother households were eligible for this allowance, but now both single-mothers and fathers can receive the allowance. The income threshold for the Child Rearing Allowance is calculated according to the number of children in a household. The income of family members other than the parent are also taken into consideration.

7.2.3 Special Child Rearing Allowance (for parents of children with disabilities)

Special Child Rearing Allowance is given to parents who look after their children with disabilities at home. The monthly allowance of child under the age of 20 is ¥50,400 for first degree, and ¥33,570 for second degree disabilities. In addition, the Welfare allowance for children with heavy disabilities is given to parents who take care of them at home. The monthly allowance is ¥14,280. On the other hand, the monthly allowance is ¥26,260 for those children who are over 20 years old. Children over 20 years old receive entitlements to the national disability pension according to their degree of disability.

Table 7.2 Family Allowances (2011)

7.3 Services for families with children

7.3.1 Day care centers for children

Municipal governments are required by the Child Welfare Law to provide day care centers for children whose parents are not capable of taking care of them for reasons such as work, illness, and care of other members of the family. Day care centers for children typically provide 8 hours of care for children aged from 0 to the age of kindergarten or primary school, but the demand to extend the hours has been increasing. The staffing and other quality measures are tightly regulated by the municipality. Fees for day care centers for children varies from 20,000 to 50,000 yen per month, according to municipality, the age of children, and the income level of the parents.

A long waiting list to enter day care centers for children is one of the urgent issues to be solved by the government, especially at the municipality level. To tackle the shortage of facilities, the municipality governments are introducing new schemes of child day care at home by women with child rearing experience or who possess a license. On the other hand, as the total number of children is decreasing, the government has been integrating kindergartens and day care centers for children since 2006.

The Cabinet Office set a special task force to solve the shortage of nursery care service in October 2010. Approximately 2.2 million children are taken care of at the day care centers for children in April 2012, an increase of 36,000 since 2011. There are approximately 25,000 children who are on the waiting list in April 2012 according to the government estimation. That number has been decreased by 731 between 2011 and 2012. However, there are still long waiting lists, especially in urban areas in relatively big cities.

7.3.2 Foster homes (for Children of DV victims and without parents or guardians)

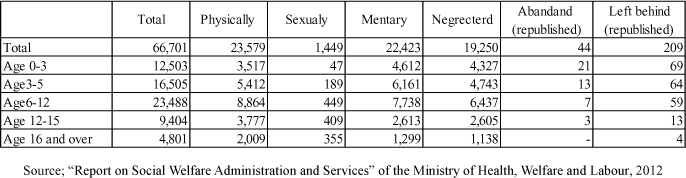

There have been increasing numbers of children suffering from domestic violence during the past decade, from 26,569 in 2003 to 66,701in 2012. Younger children are more likely to be victims (Table 7.3).

There are 58 facilities for protecting and supporting children in Japan where approximately 1,600 children were supported in 2011. An additional 4,3000 children were supported by foster parents in 2011.

Table 7.3 The number of Abuses against Children cases taken care by foster homes between April 2012 to March 2013

7.3 Work Life Balance

Japan as an “Ageing Society” was a consequence of a long declining fertility after World War II. Japanese women have a tendency to leave the labor market when they are rearing children. However, the female labor participation rate of those aged 30 to 34 increased from 74.8% in 1990 to 82.4% in 2012, and aged 25 to 29 increased from 79.0% in 1990 to 85.8% in 2012. However, there is a gap between married and single. The increase of single women’s labor participation contributed largely to raising the labor participation rate of those age groups. More women postpone their marriage in order to avoid cuts in opportunity cost by quitting their job. Therefore, the Work Life Balance measures supporting women to take both work and family responsibility became an important part of policy.

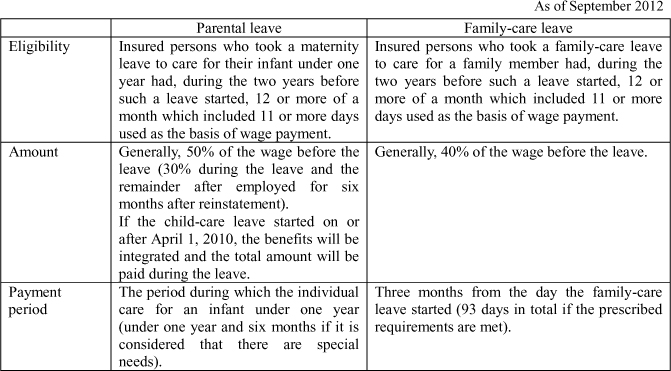

Besides promoting daycare service for pre-primary school children as well as low grade pupils in primary school, parental leave is the major support for households with children. 87.8% women take parental leave in 2011, however, among those who had the first baby between 2005 and 2009, only 38.0% of those stayed in the labor market in 2011. There are many women who quit their job after child birth and took parental leave. On the other hand, only 2.63% of men took parental leave in 2011. Therefore, the government enforces measures to promote Work Life Balance by encouraging fathers to take leave. In principle, those who have children under age one can take parental leave (see the Table 7.4).

Table 7.4 The Continued employment benefits

7.4 Public health measures for mother and children

Mother and child are protected by the Maternal and Child Health Act enacted in 1965. Health check-ups and counseling are provided by local governments to expecting mothers from the 23rd week-pregnancy and up-to three year old children free of charge. The Mother and Child Health Notebooks, called “Boshitecho(母子手帳)” in Japanese, are given to all expecting mothers. Japan's infant mortality used to be as high as 150-160 per thousand births until the early 20th century, but declined sharply since the 1920’s and attained an extreme low level below 10 in 1975. Japan's current figure of 2.3 (2011) is one of the lowest even among developed countries. This may well be regarded as a triumph of Japan's MCH policy.

Right after the end of World War II, due to the post-war baby boom together with prevailing poverty, the health condition of mothers and children deeply worsened. Under such circumstances, the Eugenic Protection Act was enacted in 1948, which authorized certified doctors to perform induced abortion on women pregnant 21 weeks or less, under the condition that the pregnancy or delivery is likely to jeopardize the pregnant woman’s health either physically or economically, or the woman became pregnant as a result of rape. The certified doctors are required to report the number of abortions performed, and if the aborted fetus is 13 weeks or older, it must be registered as still birth. The law has since been amended, and is now called the Maternity Protection Act, and the practice continues although induced abortion is and should be regarded as a last resort to terminate the pregnancy.

7.5 New perspectives for Family Policy in Japan

There were 241 children who lost both their parents, and 1,483 children who lost one parent due to the Great East Japan Earthquake which hit the Tohoku area in Japan on March 2011. According to the government report, the counseling needs were high among victims of the disasters due to the difficulties they faced during evacuation. An act for supporting children and victims of disaster2 was enacted in June 2012. This act was focused on the victims of nuclear power plants accidents.

The measures for improving the birth rate are implemented not only in the fields of social measures but also of health services. For instance, financial support for couples suffering from infertility started in 2006, which would grant the twice a year 150,000 yen operation cost of in vitro fertilization with a maximum duration of 5 years. A new scheme of compensation for delivering accidents was introduced in 2009. Lump sum payments are given to families who raise children with heavy cerebral palsy caused by delivering accidents.

The poverty of households with children is one of the major issues which the Japanese government is tackling. In June 2013, the Law on Measures to Counter Child Poverty was promulgated.

Note:

1. “White Paper on Society of Declining Birthrate 2013” (少子化社会対策白書 平成25年), Cabinet Office, Government of Japan

2. Official name is “Act Concerning the Promotion of Measures to Provide Living Support to the Victims, including the Children, who were Affected by the TEPCO Nuclear Accident in Order to Protect and Support their Lives (被災者生活再建支援制度)”